Superfest Disability Film Festival returns with hybrid events

Interim Director for the Paul K. Longmore Institute on Disability Emily Smith Beitiks was interviewed about this year’s Superfest Disability Film Festival.

Interim Director for the Paul K. Longmore Institute on Disability Emily Smith Beitiks was interviewed about this year’s Superfest Disability Film Festival.

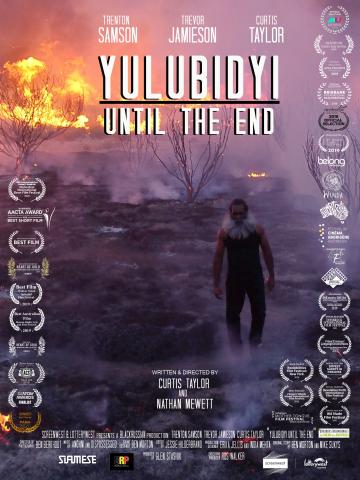

What does it mean to be a man in an aboriginal family when your brother is disabled and your father is cruel? And how do you reconcile your brother’s clear connections to land and spirit when your father wants him, and quite possibly you, dead?

Our Longmore Student Fellow Nathan Burns interviewed Nathan Mewett, Co-Director of this year's Superfest - Best of Festival Award, which will screen at #Superfest35 this October 15-17. Read on and make sure to reserve your pass to Superfest now.

Nathan Burns: What inspired you to create Yulubidyi - Until the End?

Nathan Mewett: It was a combination of a couple of things. Firstly I was writing and researching a feature film script based on disabled perspectives (something that is still ongoing). Secondly I had met and become friends with Martu (Australian Aboriginal) filmmaker/artist Curtis Taylor who was from the an area of West Australian desert near where I grew up. We had wanted to work together, specifically back home in the Western Desert regions and thought we could combine those elements with some of the elements from the feature script I was working on. The film Yulubidyi became something else entirely unique, but this is the basic genesis for our collaboration and the film.

NB: What made you decide to bring disability into this story? Did you have any personal relationship with disability?

NM: I think myself and Curtis Taylor both looked to bring something to the screen that hasn’t been seen before. With Yulubidyi in particular we both really liked the idea of ‘shining a light on disability in remote Aboriginal communities’. I personally had an interest in disabled perspectives which has since led to me doing disability support work in between my film-making practice. I have been researching disability for over 10 years and wrote my Master's thesis at the Australian Film Television and Radio School on ‘creation of disabled and Indigenous characters through a co-authorship practice’.

NB: What’s the biggest take-away you hope audiences will get from your film?

NM: I think the biggest thing is to ‘not judge a book by its cover’. This speaks to disability but also culturally in the strength of protagonist Brianol who has a cultural connection and power that belies his initial appearance.

NB: At Superfest, we often talk about disability being a creative and generative force in filmmaking. Rather than the "in spite of your disability" stories, many of our filmmakers find that their disability impacted their filmmaking and led to the unique voice or aesthetic their film brings. Does that resonate with you at all? If so, how?

NM: Yes it totally resonates. This film is 100% created through the strength of our lead actor Trenton Samson and his perspective is ingrained in every frame and helped guide the creative process. Trenton is a huge film fan who lives in the small Aboriginal Community of Jiggalong where the whole family/community help him out with his disability, so his perspective is very unique. When we first started making Yulubidyi he sat myself and Co-Director Curtis Taylor down separately and basically auditioned us by making us show him our past films (to see if we were ‘real filmmakers’). He really helped drive the whole film.

NB: How do you think your film challenges and/or improves traditional filmmaking/storytelling about disability?

NM: When researching my Masters thesis on disabled representation I came across many representations and in some ways you could argue that the character Brianol falls into the ‘super-crip’ stereotype, but I think the film challenges this (or at least brings a new perspective) by incorporating the cultural strength he inhabits and the elements from Aboriginal culture, dreaming and spirituality. On top of this there are elements to the narrative that speak to historical pre-colonial Aboriginal culture and disability. Our Noongar (Australian Aboriginal) Producer and scholar Dr Glen Stasiuk taught me early on about disabled people’s role in nomadic tribes and how they were sometimes left behind. I think these idea’s can be grasped universally as a form of metaphor, yet in terms of Yulubidyi are unique in their connection to Aboriginal culture.

NB: Yulubidyi - Until the End highlights the intersection between Australian Aboriginal cultures and disability. Please discuss how that intersection shaped both the story and the filmmaking itself.

NM: I am myself not Aboriginal so it seem’s more appropriate that Co-Director Curtis Taylor and Producer Glen Stasiuk speak to this. I can personally say that leading up to filming we spent much time in the communities involved and with their input sought to make the most authentic representations possible and tell the story they wanted and were happy with.

NB: What surprised you while making this film?

NM: Personally I found the level of community involvement in Trenton Samsons care something I hadn’t experienced before. His family travelled with us whilst shooting (a large group of cousins) yet we also had to pitch in a lot and myself and Co-Director Curtis Taylor quickly learnt how to aid in the personal care of a disabled person. Trenton is truly inspiring and surprised me daily whilst shooting. Also, for myself as a non-Aboriginal person the level of acceptance and collaboration I felt from the community (knowing my background having grown up in the region) was humbling. There was a lot of trust needed in making this film and it’s hard to describe how we got there but it was surprising and very heart warming.

NB: What about your film are you most proud of?

NM: I’m most proud of being able to give Trenton Samson the opportunity to go down a red carpet when we were nominated for the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Awards. Being able to take him to Sydney all the way from Jiggalong for the awards was a proud moment and I hope brought him a lot of joy.

NB: Film festivals like Superfest showcase those stories that Hollywood often leaves behind. What do you want to see happen next for disability in film, on both a large and small scale?

NM: I think more investment into disabled creatives and creating collaborative endeavors such as ours that put the disabled perspective at the forefront of the decision-making process is important and integral to telling authentic stories and I hope that this is adopted more. We were adamant with Yulubidyi that we used someone living with disability and not an ‘able bodied actor’ to portray the protagonist (against advice) and I would like to see this becoming the norm moving forward with disabled representations.

NB: What are you currently working on?

NM: Basically just developing lots of stuff and hoping to one day soon make a feature or long form series. I am still working on and finding disabled collaborators for the feature film script that first inspired Yulubidyi and continue my own research and support work in the disabled community whilst working on it (currently it’s called Gilding The Lily). Curtis Taylor and I have made a short ‘proof of concept’ short film called Jadai: The Broome Brawler which is currently doing festivals - It is a boxing film based on Curtis’ grandfather and we are developing a feature film version. I have also written a treatment for a feature film version of Yulubidyi that would be great to make someday but would take a great leap of faith and trust from investors to make correctly.

-

To check out Yulubidyi - Until the End at superfest, get your passes now and watch at any point October 15-17. Free passes available!

In the 1980s a disabled terror group reasonable adjustment carried out a campaign of violence to gain rights - or did they?

Our Longmore Student Fellow Nathan Burns interviewed Justin Edgar, director of Reasonable Adjustment, which will screen at #Superfest35, October 15-17. Read on and make sure to reserve your pass to Superfest now.

Nathan: What inspired you to create Reasonable Adjustment?

Justin: First and foremost, the thing to make sure all potential programmers know is that the film is not real. It is entirely a constructed fiction made with actors, digital effects, different film stocks and sound techniques of the period and some deepfake footage of real people. There is a lot of invisible effects work in this film.

As a filmmaker, I find mock documentary films don’t really convince so I set the challenge of convincing myself. I had to go to great lengths to do that. It wasn’t easy to do and everything in the film had to be recreated. I made microfiche newspaper articles, burned the chair for real and hired a professional reportage photographer to shoot 35mm ektachrome stills, these photographs were then shot on a 16mm rostrum camera exactly as would have been done back then – you can’t just do that anywhere. We had to source period props, costumes and digitally remove anything that didn’t belong in frame. There is a lot of invisible CGI in the film. We also went to a home office registered firing range in Yorkshire to recreate the attack on the BBC using live ammunition. To get the right locations we had to shoot in the Midlands, Birmingham and various locations in London including a guerrilla shoot in Westminster. We also had to find a voice double for Margaret Thatcher.

We shot on 16mm film with an Arriflex camera that would have been used at the time. We used vintage lenses and old-fashioned tungsten lighting. We made the sound mix mono and used special sound filters to ensure it sounded of the period. I auditioned many actors to get someone with the right inflection of a presenter from the 1990s. This authenticity also extended to the accessibility features of the film and it has old-style Ceefax subtitles.

Part of making it work was the tone – I decided it should have a slightly left-wing journalistic bias which would help to ensure that it felt real. Many British TV programmes of the time had that stance and World in Action is how filmmakers like Paul Greengrass started out. If you look back at old docos from that period they are very mannered and slow as well and we tried to emulate that style.

I realised that pre-2000AD we were BG (before google) and truth BG is hazy, you can make stuff up. For instance, in 1997 I was involved in quite a big news story, it made national press at the time but it’s nowhere to be found online. For all intents and purposes it doesn’t exist. Before Google is the dark ages in terms of what really happened. Another example is the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) who were very active, and are kind of the model for RAD. They sent letter bombs, killed and even branded people with branding irons, but you never hear anything about them now.

I have a theory about protest groups – they assimilate the tropes of other, past protest groups, so are quite easy to recreate and emulate. Putin has done this to great effect in Russia to steer and influence public opinion.

I believe we are living in a post-truth era, whether we like it or not. I also believe that truth is relative and a subjective concept, we all live in our own realities and cinema reflects that. Susan Sontag spoke of humankind revelling in “mere images of the truth”.

Nathan: For our mostly US-based audience, can you share a bit more about the cultural context of disability in relation to radicalism in the UK? Relatedly, was there any significance to the fact that you borrowed footage from the IRA?

Justin: I think outside the UK we have an image as a polite little island, but its actually always been a hotbed of anti-establishment movements. The French called it a revolution but we call ours a civil war! From the Tolpuddle martyrs to Punk to Brexit, there is a long history of dissent, its in the DNA of the British. I grew up in the Thatcher 80s, a very febrile era of mistrust where peace activits and trade unionists were under mass surveillance by the state and the spectre of IRA violence hung over everything – there were metal detectors in my local library and bombings were common. I think a lot of that went into Reasonable Adjustment.

According to the British Medical Journal there have been 130,000 preventable deaths attributable to the austerity policies of the Liberal Democrat and Conservative government of David Cameron and Nick Clegg since 2010.

Errol Graham, 57, weighed 28.5kg when he starved to death after complications owing to the nature of his disability led to his benefits being cut. He died having pulled out his own teeth with a pair of pliers as he didn’t have the appropriate care.

These are holocaust-like numbers more associated with war than social policy and people need a mirror held up to the society we are living in. A society where disabled and disadvantaged people have been disregarded and vilified by a government which we voted in. This is life and death, it’s a big subject and the work needs to be impactful”.

That is why I compare the struggle for disability rights to other armed resistance groups with RAD. I wanted to compare the two and draw parallels.

Nathan: What’s the biggest take-away you hope audiences will get from your film?

Justin: If we start with the notion that truth is tyranny, we can understand the film better. I appreciate not everyone will agree with that assertion, but there’s no point in making a film if it doesn’t cause debate. Whenever you point a camera at something you are making a judgement about how you see that thing, staking your own sense of truth upon it.

Who is the arbiter of what’s real and what isn’t? Yourself? Can you trust yourself?

My reality may not be your reality.

Another important point is that this is satire and people have to remember that, it’s meant to make a point through humour. When I put a teaser clip of the film on Facebook it was viewed 80,000 times in 24 hours and was banned by facebook for hate speech. I always felt it was interesting for people to find their own truth about what they are watching, good or bad. After an appeal it was reinstated as it makes a comment on hate speech rather than extolling it.

The key question that I hope viewers will ask is why make it up? Why bother? And that question prompts you to delve a bit deeper. I encourage programmers to let audiences make up their own mind about the film. I always knew there was a risk that people would get offended if they felt stupid, that they’d been duped. But then I thought in that realisation there will be an insight where people think about the issues at hand…

Nathan: At Superfest, we often talk about disability being a creative and generative force in filmmaking. Rather than the "in spite of your disability" stories, many of our filmmakers find that their disability impacted their filmmaking and led to the unique voice or aesthetic their film brings. Does that resonate with you at all? If so, how?

Justin: Absolutely, I believe that mainstream culture survives and thrives on the fringes and that is what we bring to the table as disabled filmmakers – a unique voice and world view. I think there is an increasing argument for a school of disability filmmaking and I’m currently writing a book on that subject.

Nathan: How do you think your film challenges and/or improves traditional filmmaking/storytelling about disability?

Justin: It seems to me the traditional depictions of disabled people in narrative film is either as a villain or a victim. With Reasonable Adjustment I wanted to depict disabled people acting in a way which was questionable and challenged the traditional moral values of the audiences. The film actually began life as part of an exhibition for the Richard Attenborough Gallery in the UK and what was interesting as I eavesdropped on conversations of the gallery visitors was how people thought the group were justified in their actions!

Nathan: What surprised you while making this film?

Justin: I was surprised at how the film was received. It premiered as part of an arts festival at the Southbank Centre which is a major art space in London. It had 60,000 views in one weekend and was actually banned by facebook because some people objected to the language used on grounds of hate speech. We were able to get it put back up though. It was also banned by another festival in the UK because it was seen as controversial. I think people are used to different kinds of depictions of disabled people and it is hard for them to process depictions that are not the norm. It's interesting that the people who objected to it are by and large non-disabled.

Nathan: What about your film are you most proud of?

Justin: I am proud we got banned from Facebook! I’m also proud that it works – that people think its real. There was a lot of sleight of hand involved and I’m glad that the efforts we went to paid off.

Nathan: You handled the audio description of Reasonable Adjustment yourself to make it match the tone of the film. Please share anything you’d want your audience to know about your approach and process.

Justin: For audio description we invented our own automated version purportedly devised by Texas Instruments called TalkTextTM, the audio description track for the film gives its own narrative, designed to reflect ableist attitudes and language of that time. I think audiences should listen to it, as it tells us a lot about how far terminology has come in the last 30 years.

Nathan: Film festivals like Superfest showcase those stories that Hollywood often leaves behind. What do you want to see happen next for disability in film, on both a large and small scale?

Justin: The key is getting more disabled filmmakers behind the camera, for example everyone talks about CODA* but why wasn’t the director/writer/producer Deaf? The filmmaking community needs to stop taking it for granted that disabled stories can be authentically told by non disabled filmmakers and it's our job to constantly challenge that notion.'

(*Editor's note: This refers to a different CODA than the film screening at Superfest 2021.)

Nathan: What are you currently working on?

Justin: I’m producing four disability shorts for Film Four here in London. It's really exciting they are backing disabled film talent and the films are all on the theme of Love and will premiere on Valentines Day!

To check out Justin Edgar's film at Superfest, get your passes now and check it out any point October 15-17. Free passes available!

What can we learn from the most despised insects about lockdown and embodiment? This film celebrates the ingenuity of a disabled filmmaker who is grappling with the pandemic and working with the actors he had access to.

Our Longmore Student Fellow Nathan Burns interviewed Raju, the director/producer/writer of An Apparition, which will screen at #Superfest35 this October 15-17. Read on and make sure to reserve your pass to Superfest now.

Nathan: What inspired you to create An Apparition?

Raju: On March 19th 2020, the COVID pandemic forced all the citizens of India into a twp day lockdown. The prime minister of India addressed the whole nation and everyone felt very positive and expected some good news, as everyone was under the perception that the two days lockdown would be enough.

During his address, the prime minister has declared a complete lock down in the whole nation for all the services excluding few emergency services and everyone went into a shock as everything is going to be at a stand still. But for me, a victim of GB syndrome, which I suffered while I was shooting for a film, it was just the regular norm. I was bedridden for so long it became habituated for me and was not a total shocker, the only bad thing for me was cinema halls would be shut.

My routine was following covid news, and tracking what's happening around and seeing the numerous deaths. I was in a disturbed state. One fateful night when I woke up to drink water and switched on the lights I saw two to three cock roaches under my bed which went into hiding as soon as I got up. I used to watch them for the next few days.

Until the GB syndrome attacked me I had a dream of making interesting movies but the GB syndrome took a toll on me mentally and physically as it took 3 years to walk by myself. But the dream of making movies didn't die within me.

During the lockdown, cockroaches helped me in generating the idea. I used to follow the news in which there were numerous instances of people violating the lockdown rules.

Nathan: What’s the biggest take-away you hope audiences will get from your film?

Raju: In a country such as India, unifying every citizen is not possible but the pandemic made every citizen of the country freeze their activities. There are people who disobey rules but the context is also important. In such a grim situation one disloyal person could cause severe damage to not just fellow citizens but also his or her family members by spreading COVID. I wanted to portray the impact of such diffidence. Cockroaches are not creatures that can roam around freely and if they come out into the open there is a huge threat for their life. I wanted to show that people are no different in such situations; they can cause huge threats by not obeying social distancing and spreading the pandemic.

The COVID pandemic, especially in the second wave (May-June 2021), has caused huge damage in India because people did not follow the precautions laid out. I wanted people to understand the same well ahead and take precautions, and if even few were impacted by my film I would be glad.

Nathan: At Superfest, we often talk about disability being a creative and generative force in filmmaking. Rather than the "in spite of your disability" stories, many of our filmmakers find that their disability impacted their filmmaking and led to the unique voice or aesthetic their film brings. Does that resonate with you at all? If so, how?

Raju: The last project that I had done when I was completely active was a student project work for CalArts. During the shoot I was affected with GB syndrome and that mentally crushed me. I always wanted to make movies on the deepest issues that concerned India by travelling to remote parts of the country. But, after being bedridden, I have lost the confidence that I can work again on my own.

I have regained my confidence through “An Apparition.” As the film made it into some respected film festivals, my thought process and my confidence level changed enormously. My emotional thoughts have changed a lot since 5 years ago. I am now able to connect to a myriad of subjects emotionally. I always thought of making films for the world but disability made me realise the essence of filmmaking - to make films that you like.

My thoughts are now more clear, I am able to understand a problem holistically, and connect to emotions very strongly. I believe that these traits have developed within me due to the disability I have.

Nathan: An Apparition was a result of pandemic restrictions in India and the resources you had at the time. How have these limitations forced you to be more creative with your filmmaking?

Raju: To start with, I initially had only a basic idea without any proper script but I understood during my film course at FAMU (Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague) that filmmaking was never about portraying a story in a predetermined, cinematic way. The major weapon ruling the human brain was the mobile device but the limited cockroaches which I had in my home won't be enough to explain the story, so I have contacted 10 -11 of my friends from non-film background and asked them to shoot random videos of cockroaches.

The only question everyone asked is why? For which I had no answer as I had no story in my mind apart from the basic idea of common point between humans and cockroaches. Everyone felt disgusted or funny after asking them to shoot random videos. Surprisingly after one week around five members believed in me and sent me the videos. Some of them sent me the videos in portrait mode. The only responsibility I took as a director is to tell my friends to take the videos in landscape mode so that it would be feasible for editing and everyone obeyed. All the shots were taken in very basic models of smartphones.

Nathan: Most people think “ick” when they think of cockroaches, but there’s a resilience that resonated with many of our jury members. Did you feel that connection? What prompted you to submit this film to a disability film festival?

Raju: Cockroaches are thought to be an entirely alien species by humans; we tend to not include them in any sphere of our life. I trust that every being, micro, small or big, has the same life within it and I look at all beings as the same. This philosophy of mine might have stemmed from the various experiences that I had in my life.

When I discussed this idea, many were reluctant to the idea of cockroaches being the central subject but I did not change my idea nor was I disheartened and instead I looked for people and places where my film would be welcomed. The very aspect that this film festival is dedicated to special people made me realise that the so called “off-beat” subject of my film would not be frowned upon by the people that overlook this festival. I was also confident that my film would be judged objectively without drawing parallels from other yardsticks.

Nathan: What surprised you while making this film?

Raju: The predominant notion is that to make a film you need a structured setup such as crew, technology, equipment, a proper script and a person who can balance all these. But neither before the start of this project nor while executing it I thought of all these drawbacks. I wanted to make a small video that deals with the contemporary issue by drawing a parallel between the most disgusted creature on the planet and human beings. The project could also have been executed by using animation or in other ways but I wanted to portray the nature in its raw essence.

What surprised me is the way my friends with no film background provided me with some stunning visuals – stunning in the sense that they were complete and provided me with the exact visuals that could convey my intentions. This made me realize that art is not restricted but it exists everywhere, and art is subjective to experiences not to knowledge or expertise. Additionally, I also understood that a person no matter where he is, locked up or free, can come up with creative thoughts and execute them well, all he or she needs is love and affection from his close ones.

Nathan: What about your film are you most proud of?

Raju: I loved experimental movies and the satisfaction/happiness that I gain in making them liberates me from the physical bondages, and I feel like I am a bird soaring up in the sky. When I was completely fit, I made a film “Slightly Mad,” which took about 2 years to complete and it was not selected in “BRAINWASH Film Festival.” Fast forward a few years and “An Apparition” made it into the same film festival. This boosted my confidence. As a filmmaker I may not appeal to everyone but art makers thrive on the accolades of others so I cannot completely discard the fact that I need to be motivated at times by appreciation and your selection helped a great deal in that aspect.

Nathan: Film festivals like Superfest showcase those stories that Hollywood often leaves behind. What do you want to see happen next for disability in film, on both a large and small scale?

Raju: Every art form has a platform to encourage it but it may not seem ideal to everyone. I trust that festivals that cater to specific needs or consider the situations of the film makers are rare. A disabled person can only achieve something when he/she is encouraged and only when the society makes him/her feel that he is on par with all the others he/she can feel comfortable with the situation.

Developed societies have better infrastructure and sentiments in place that encourage people with disabilities, but in many other countries disabled people struggle even for basic identity and a chance to compete. Struggling for trivial things such as getting out of bed, travelling, etc. may not be a huge burden for common people but for us those are nothing short of herculean. If we want to alleviate at least some of these concerns, empowering us with an opportunity to work in our field of choice is the only way out.

Filmmaking involves risk and money. When we invest money in the projects, support from festivals such as “Superfest” make us feel more comfortable. When you know that your work will be appreciated you will risk investing money in it no matter what the economics are. Everyone starts with a tiny, first step and encouragement from organisations such as yours boost our morale a lot.

Inequalities are universal. While some can be alleviated by way of dialogue others need action. In the creative field such partiality abounds. We can only walk where running is required from us so, we are left behind in the race by the industry. Cinema is a huge deal and we cannot make it by sitting at a single place but if we are not encouraged by our contemporaries we cannot proceed ahead even at a snail’s pace. If the environment is not conducive enough, no matter how strong we believe in ourselves, a breaking point eventually arises.

Institutionally, I would like to see some policy changes such as reduced tariffs, a mandatory disability column in all applications and a separate recognised community for ourselves. Most important of all, a platform for sharing our experiences with the bright minds of the industry, I believe, would do a great benefit to us all.

Nathan: What are you currently working on?

Raju: I have in stock 2 to 3 different abstract ideas and of those, I would like to select one particular idea and work on it differently. I want to work and execute a project that is extremely novel and sets a paradigm. As the budget that I can garner is limited, I would need to collaborate with talented, young people who are willing to put passion ahead of monetary benefits. The work flow is to ready the script, and at the same time improve my technical expertise. My film studies, to a large extent, will help in this aspect and I tend not to focus on my disability on working on my project as I believe that I can execute any script. That is the driving force for me and I trust that I can compete with anyone out there.

-

JOIN US FOR AN APPARITION AND MORE AT #SUPERFEST35: SUPERFESTFILM.COM/SUPERFEST-2021