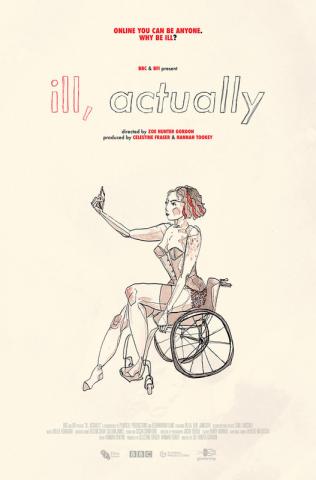

Superfest Spotlight: A Q&A with the Producer of 'ill, actually'

This short documentary explores the challenges of being young and chronically ill in a carefully curated online culture. A real life "Superhero," a YouTuber and a Camgirl explain why they choose to share - or hide - important parts of who they are online. Our Longmore student fellow interviewed Celeste Fraser, the producer, to learn more about her thinking behind this exciting film.

Nathan Burns: What inspired you to create ill, actually?

Celeste Fraser: When I first became ill, I spent a whole year in bed and during that time I watched a lot of films. I was eighteen at the time and finding myself drawn to coming-of-age stories, I suppose because I was seeking escapism, but after a while these actually made me feel more isolated because I just couldn’t relate to them: they were all non-disabled storylines. I started to scour the web for films that might reflect my own experience, but there was next to nothing to find — especially about invisible disabilities. So I think I knew then that as soon as I was well enough, this was the film that I needed to make. Of course, it was still only a blurry idea at this stage, but Zoe Hunter Gordon, my director, was keen to turn it into a reality so together we developed the film over three years. I’d like to pretend that ill, actually was born from a pure desire to make art or activism, but honestly I think I just wanted my friends and family to better understand me.

NB: What’s the biggest take-away you hope audiences will get from your film?

CF: I hope the biggest take-away is that disability isn’t a tragedy. Sure, it can present a host of challenges (and the world is certainly deeply ableist!), but ultimately life as a disabled person is as complex, joyful and nuanced as life without a disability. I hope that Ben, Bella and Jameisha’s varied perspectives show that there’s no “right” way to live with disability and that it’s in no way a barrier to a meaningful life. And of course I hope, maybe most of all, that people see that illness and disability are so often invisible: you can’t see someone’s whole life just by looking at them.

NB: At Superfest, we often talk about disability being a creative and generative force in filmmaking. Rather than the "in spite of your disability" stories, many of our filmmakers find that their disability impacted their filmmaking and led to the unique voice or aesthetic their film brings. Does that resonate with you at all? If so, how?

CF: This is really interesting and it certainly feels true of our contributors: Bella, Ben and Jameisha have all forged their own unique careers not in spite of disability, but precisely because of it.

Bella is a camgirl because she can’t work a traditional 9-5; camming allows her to work flexibly and, as she puts it, she can “do it lying down.” Ben has become a personal trainer because fitness has had a profound positive impact on his own life and health. And of course Jameisha has founded a platform which creates content about chronic illness and provides community for those going through similar experiences to her. Their disabilities are an essential part of who they are. As to my role as producer, I think that my having a chronic illness certainly helped potential contributors feel more at ease in opening up to us about their own illnesses. Over many months, we had over a hundred exploratory phone conversations with young people with chronic illnesses and disabilities, and it was a weird and wonderful privilege to be able to connect with these perfect strangers over the phone. We shared our most intimate stories, experiences and even symptoms with each other. And though we could ultimately only feature three contributors in the final film, each and every one of these people who volunteered their time and energy to speak to us on the phone contributed in a meaningful way to the film being what it is today. I don’t know if this would have been possible had I not had a disability myself, because I think that reciprocity with the filmmakers is important — it seems only fair to meet vulnerability with vulnerability.

NB: How do you think your film challenges and/or improves traditional filmmaking/storytelling about disability?

CF: So much storytelling about disability begins at diagnosis and ends in death, in a cure, or in the disabled person becoming a hero to society through some extraordinary achievement (ie. the Supercrip” trope). So it was essential to us that though our contributors are all impressive in their own individual ways, our film evoked neither pity or inspiration. If the audience feels pity or inspiration, then you know that the disabled protagonist is being portrayed as an Other: they are being represented as “not like the rest of us”. And being portrayed like this means the disabled character is basically no longer seen as human! So I actually love the idea of non-disabled people watching ill, actually hoping for an uplifting little boost of inspiration porn, but then to come away a bit miffed that we didn’t give them what they expected! In my eyes, if the non-disabled viewer isn’t inspired, that means our disabled protagonists are three-dimensional — and the film is a success.

NB: What surprised you while making this film?

CF: I certainly had no idea that through the process I would gain a completely new understanding of my own identity as a disabled person. In truth, meeting Bella, Ben and Jameisha —and speaking on the phone to over one hundred other young people with chronic illnesses during the long development process— totally changed my relationship with my own identity. Before making the film, I had never really identified as “disabled.” My life was a bit different from my friends.’ and when it came to things like university I counted as a “disabled student,” so I guess I knew that I was disabled, technically, but I was too shy to openly say it. I think I worried that if I identified that way, people would think that I had “surrendered,” somehow, and that I was no longer striving to “get better.” I had internalised the belief that illness is something you have to “fight,” and that I would be judged for making peace with my body as it was. It didn’t help that I’d had doctors refer to how other patients with my condition “became disabled” when they did this or that — as if disability was the result of bad choices! Learning about the social model and meeting young disabled people like Bella and Jameisha who were involved in activism and disability justice, taught me that I am disabled: not by my conditions, but by society. So I no longer feel it’s me versus the world — I know there are loads of us. I’ve got the film to thank for that.

NB: What about your film are you most proud of?

CF: Zoe and I had been researching and developing the film over three or so years, but when it finally got commissioned we were given an extremely short production turnaround of around

six weeks to make it. It also fell over Christmas and during a health flare of my own, and of course our contributors’ conditions were also fluctuating in nature, so it was an intense production period. I’m really proud that in those crazy six weeks, we managed to achieve the film we had set out to make three years before. Film festivals like Superfest showcase those stories that Hollywood often leaves behind. What do you want to see happen next for disability in film, on both a large and small scale? To be honest, I’m tired of all those conversations about access and inclusion when really we want so much more than that! We all already know that having some limitations helps the creative process — and that applies for everyone. So I think that disability genuinely does enhance creativity, and in film I do believe there’s such a thing as a Disabled gaze. So I would love to see, for example, how deaf/ Deaf-led filmmakers might revive the lost art of silent cinema, or how a wheelchair-using director doubles-up their chair as a built-in dolly, or how captions and audio description can be played with to add a whole extra dimension to a film. So it’s frustrating that the conversation is still very much about our “seat at the table”, when in reality, given half a chance, disabled filmmakers would bring so much creativity, novelty and ingenuity to the form. I’m over here waiting for a Disabled New Wave.

NB: What are you currently working on?

CF: At the moment, Zoe and I are collaborating on a short fiction film about ableism and sibling relationships. To be honest, it feels like the first fiction film where I feel I’ve actually seen myself represented! I’m really excited about it. We’re hoping to shoot this autumn.

-

To check out Ill, Actually at Superfest, get your passes now and watch at any point October 15-17. Free passes available!