Superfest Spotlight: A Q&A with the filmmaker of Ecstasy

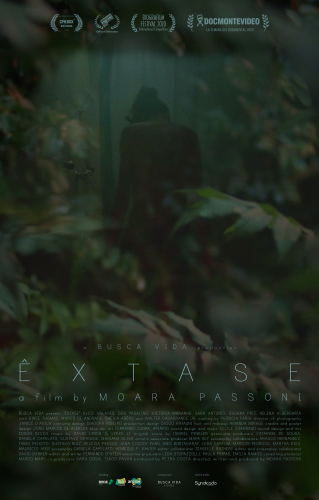

Alt text: Poster for Ecstasy. A woman stands with her back to the camera, with the image slightly transparent over a shot of foliage. Light colored text reads the film title and credits in Portuguese.

In Ecstasy, an elliptical non-fiction film, anorexia becomes a way for Clara to challenge womanhood and find a place in an uncertain, surreal, and brutal world. Racked with anxiety in the chaotic political landscape of 1990s Brazil, Clara finds solace in starving herself, experiencing both rapture and torture. Longmore Student Fellow Olive Patton interviewed Moara R Passoni, the filmmaker, to learn more about her thinking behind this exciting film.

Olive Patton (OP): The imagery around the blue dot is so powerful. Where did this idea stem from, and what was the message you wanted to express?

Moara R Passoni: (MP): To answer this question I need to give you some political/social context about Brazil.

I’m a daughter of an activist involved in social movements in Brazil at a time when fighting for civil rights was considered a crime. My mom, Irma Passoni, was fighting for civil rights during the military regime (1864-1985).

During the dictatorship, she became a congresswoman (one of the few at a time when politics was even more chauvinistic than today).

At around this time, I was born in the Jardim Angela neighborhood of São Paulo, which was culturally effervescent, but impoverished. Already during the military regime, the militias were operating in the neighborhood, and, in the 90s, it was completely overrun by organized crime. It was the most violent neighborhood in Brazil for almost an entire decade.

(Today, it is once again a neighborhood of huge cultural richness, with Cooperifa, Sérgio Poeta, Mano Brown, Racionais MC’s, Santo Dias, and many others.)

So, I grew up with a mother who, on one hand, had politics as her main ‘lover’, yet whose life was constantly in danger. For example, my house was invaded and robbed seven times as a reprisal for her activities in the region. And I would live in a permanent state of anxiety, never knowing if my mom would come back home, if she'd make it through another day, etc.

So, in order to find some comfort in those circumstances, and have some control over what cannot be controlled, I started developing magical thoughts.

The blue dot was the way we found to concretize those invisible mental strategies.

But it also transcends that reality.

For me, it became Clara’s desire. She fights with all her strength to eliminate it. But it will eventually win the battle over her.

As we wanted it to feel alive, it was painted in watercolor, and in different layers, which were then animated.

And I chose a certain tone of blue that, applied over the pale, skin-colored palette of the whole film, could evoke the feeling of anorexia.

OP: This film feels very personal, and I love the way you explore the topic of control. I grew up in a dance studio doing ballet and always struggled with the art's uniformity, structure, and precision. Ecstasy layers that with a young girl exploring her sexuality all while living without political stability in her country. Clara’s character is complex and adds dimension to the stereotype of an unhealthy ballerina. What aspects of her story did you find crucial to include for the audience to understand her point of view?

MP: Clara is a character created from my own experience of anorexia from 11 to 18, crossed with experiences of other women who lived through the same thing.

Even though each ordeal is different, I wanted to understand how my own experience of anorexia was related to other women’s experiences. So, for more than two years, I maintained contact with people going through the same thing I had. Some of them gave me their intimate journals and diaries. One of them – who asked not to have her name revealed – collaborated on the screenplay directly, suggesting scenes, reading the voice-over as we advanced with the editing and the writing of it.

You are not an ‘anorexic’ growing up. You are a person growing up at the same time as you fight anorexia. Each experience of suffering is different. And, in my case, it was a kind of ‘solution’ to unvisited pains. And a huge part of that, which I can now see I was investigating, is the complex imbrication between subjectivity and power.

It was a kind of mental trap that invisibly intensified the pain – even though I ‘didn’t feel it’ at that time.

Anyway, the film is built in so many layers… What maybe is important to highlight is the uncanny seduction of anorexia.

In my case, I thought I was searching for ecstasy. And it took me years and maybe a whole film to understand that I was invested in a narcissistic search in which the sought-for ecstasy wouldn’t mean openness, but intense closure. The pain had ‘disappeared’ because the other had disappeared. And in a deeply solitary existence, ecstasy, if accomplished, would mean death. And I’m glad this enchantment was broken by the ‘anorexic's’ biggest enemy, which, for me, was desire, hunger, openness.

OP: While watching Ecstasy and understanding the context of the political climate in Brazil at the time, it felt similar to the loss of rights we are currently seeing in the United States. With Roe v. Wade and the conversation of losing access to birth control, do you see this film being relevant in times when women/trans/non-binary/disabled/poor/BIPOC folks are losing the right to their autonomy?

MP: I hope so! The way I see this is: in anorexia you respond to the patriarchal control over your body with more control. It could be seen as a kind of radicalization of that control.

But also as a rebellion: ‘no one will control my body more than I do'. In other words, it can be seen as a rejection of the patriarchal power over our bodies.

And there is one more aspect to it. I remember once feeling I’d show in my body, with my body, the consequences of this patriarchal control. As if my anorexic body was, aesthetically, a tragic ‘mirror” of this society.

OP: The main character Clara ends up being hospitalized and experiences medical gaslighting. Why did you want to include this in the story?

MP: Because not being heard by doctors was part of my experience and that of some of the women who collaborated with me. For example, I once went to a psychiatrist who said: “If you don’t eat you’ll die.” I just thought to myself: this person doesn’t understand much of what someone experiences when in the trap of anorexia. What I felt at the time is that I was a kind of super powerful woman. I knew the risks. But death had no concrete meaning for me.

Doctors will also often assume that you are manipulating the situation. And you probably are. However, that’s not sufficient reason not to listen to someone’s suffering. The same collaborator I spoke about earlier had her intestines perforated due to force-feeding, because the doctor thought she was lying when she complained about the pain, just to avoid being fed.

I don’t know how many doctors I went to see. It was the doctor who first named what I had: “anorexia”. That was just a word for me at the time. Like death, it didn’t mean much. But after attending so many doctors, I started relating to my own body in a “medical” tone. And I knew more about nourishment than the nutritionists—simply because it was an obsession. And that made me listen to doctors or nutritionists with a certain indifference or even arrogance.

The first doctor who really helped me was a psychiatrist and a therapist. She never spoke about food with me. She never asked me if I had eaten or not - she probably knew I’d lie.

But she was doing with me what I did most of my time when I was 15-16-17: we read. And reading books such as “Alice In Wonderland”, “Alice Through The Looking Glass” and “The Land of Painted Caves”, as well as other texts from Elias Canetti, etc., she was brilliant in “breaking” the control I had over myself.

One day, I woke up, in the middle of the night, absolutely famished. And from that moment on, I could not not desire anymore.

Alt text: A young woman with light skin and light eyes wearing a grey shirt lies on the ground on her side, looking at the camera.

OP: Throughout the film, other characters discuss Clara’s femininity and womanhood, and she is upset about the prospect of getting breasts. The journey she goes on pushes boundaries on typical expectations, like kissing girls and starving herself to the point she loses her period. What aspects of womanhood and growing up did you want to showcase in your film?

MP: I wanted to showcase how overwhelming it is to deal with the transformations of your own body when you are a teenager in a society that is moralistic, repressive, patriarchal… We do not learn to desire. We learn to fear. And our body is the first place we exercise that. Fear and disdain.

I wanted to disappear.

I wanted to be ever smaller than I was; shrink down to the bones: that, for me, was a safe place. The clarity of the structure. The lines. A kind of ‘relief’ from the shape in opposition to the confusing shapes of the viscera, organs, blood, meat. I wanted to find the shape of control even more than I wanted to have control over the shape.

OP: I love the scene where the mother is tenderly drying herself off after a bath. That tenderness also comes back at the end as the mother and daughter sit on the couch. Was there a process of self-care/processing in making this film? Was it cathartic to show moments of love and intimacy with one’s body?

MP: Yes. And the mother’s body is life, it is comfort. But it can also be scary for a fully developed woman’s body.

But I do believe the biggest point in the arc of Clara’s character is this kind of reconciliation with the mother.

During anorexia, after trying to become the mother of my mother with my magical games and my feeling responsible for her life, I decided to reject her, and I did that for a long time, as if by doing so I’d somehow solve the pain of her absence.

Gladly, I couldn't go till the end with my “plan”. Mother’s love is the most impressive, strong, crazy, fascinating, disturbing – and necessary – form of love I’ve experienced.

OP: How do you see the connection between eating disorders, anxiety, and disability? In other words, what does it mean to you to have this film screen at Superfest, a disability film festival?

MP: For me, it is a huge opportunity and an honor to participate in the disability film festival.

I made this film to ask questions about a kind of suffering that is extremely common but underestimated, simplified, and stigmatized. Disabilities are part of everyone's life. It's not something outside life. Anorexia, for me, is a magnifier that allows us to see invisible aspects of the society that everyone experiences and suffers from to some level, but which, in this kind of suffering, are radicalized.

So, it is an opportunity for all of us to think about ourselves, to transform what oppresses us all.

I hope it will be a contribution, a tool for the conversation about eating disorders, anxiety, disability, and mental health.

For me, an eating disorder is an extreme experience of anxiety with another name and specific characteristics. To the point that it makes you afraid of life, of love.

Not sure it is possible to never be afraid of these, but it is certainly possible not to guide all your actions by fear.

OP: So far, how do you feel about the reception of your film? What do you want our Superfest audience, especially our disabled supporters, to take away from Ecstasy?

MP: The film opened at CPH:DOX, screened at Doc’s Fortnight at MoMA, Cinema du Reel, and so many other amazing festivals… It won seven awards. Many articles were published. There are at least four people writing about the film for their Masters or PHD’s, or in magazines etc… both in cinema and in mental health.

I’d like to ask the audience of Superfest to just allow themselves to live the film as an experience. It is not a traditional narrative at all. It is not an easy film. Because of the subject, but also because the film refuses to simplify the suffering of anorexia.

I hope the audience and the disabled supporters will leave the theater with a lot of questions.

And that the film may continue resonating and living with you through your conversations after the screening.